I’ve talked a lot over the years about Roth IRA conversions, but do they make sense when you are already retired? And if so, what’s the best strategy to bring about the conversion?

We received an Ask GFC question that refers to both topics:

“I have 300K in a former employer 401K. I am 69 years old. Preparing for the RMD (Required Minimum Distributions) in 2 years, I am thinking of moving some 401K to a Roth before then. Can I

do the following:

— Move $50k from the 401K after the 4th Q distribution (so I get that income), but before year end? Assume distribution is 12/23, get distribution, then move 401K 12/28 for tax hit this year.

— Move $50k from 401K sometime next year for tax hit next year.I may move more depending on how the tax hit plays out, will analyze that.”

For the most part, doing a Roth conversion is usually a good idea, no matter which side of the retirement line you’re on. And spacing the conversion out over several years is usually the best strategy. But let’s discuss the specifics since doing the conversion in retirement might add a wrinkle or two to the process.

Table of Contents

The Benefit of Doing a Roth Conversion in Retirement

Since withdrawals taken from Roth IRAs are tax-free, this is the most obvious benefit of doing a conversion. By converting 401(k) funds to a Roth IRA, the writer is exchanging a taxable income source for a tax-free source. The tax implications, however, aren’t always a pure play, particularly in retirement, but we’ll get more specific with taxes in the next section.

The next biggest advantage of a Roth conversion – in fact, maybe the biggest in retirement – is that Roth IRAs don’t require required minimum distributions (RMDs).

Why is that such a big deal?

RMDs are the method that the IRS uses to force funds out of tax-sheltered retirement plans and into taxable income. After years of accumulating tax-deductible and tax-deferred contributions and earnings, RMDs represent tax payback time.

RMDs are required once you reach the age of 73. At that point, each plan must begin distributing funds based on your remaining life expectancy at the age of each distribution. In theory, this will mean that from age 73 to, say 90, your retirement plan will be roughly depleted, or very close to it.

That becomes an obvious problem if you live past 90, which is no longer uncommon. But you will arrive at that age with greatly reduced retirement assets.

Since Roth IRAs don’t require RMDs, they are almost certainly your best hope of not outliving your money.

In the same way, Roth IRAs are an excellent way to preserve at least some of your retirement assets to pass on to your heirs upon your death. While traditional IRAs and other retirement plans generate a tax liability for your heirs (because of RMDs), Roth IRAs don’t generate taxable income.

So there are clearly compelling reasons for converting a 401(k), or any other tax-sheltered retirement plan, over to a Roth IRA.

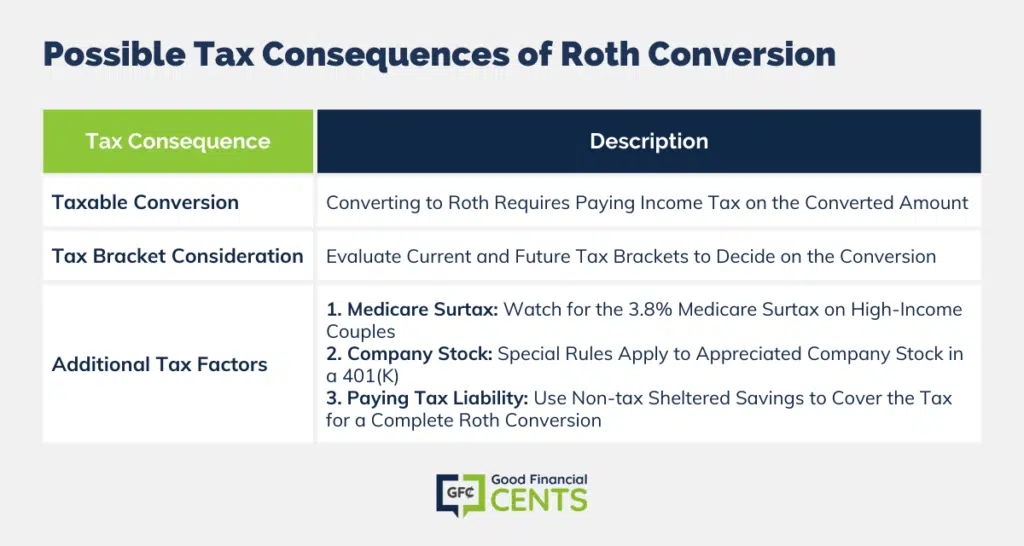

The Possible Tax Consequences of This Roth Conversion

In order to get the tax-free income that a Roth IRA provides, you first have to pay regular income tax on the amount of money that you convert from other retirement plans. Once again, distributions from any retirement plan – other than a Roth IRA – are subject to income tax.

By converting $50,000 of his 401(k) plan to a Roth IRA, the writer is adding $50,000 to his taxable income. If as a result adding that amount to his other taxable income puts him in the 25% tax bracket, then he will have to pay $12,500 on the conversion. Any state income taxes will add to that liability.

This is where you have to evaluate your current tax situation compared to what you expect it to be in a few years. The writer is 69 years old and doesn’t indicate if he is retired or if he’s still working. That creates an extra consideration.

If he is in anything greater than the 15% tax bracket but expects to be in a lower tax bracket after turning 73, he might not want to do the conversion right now. That is especially true if he does have employment income.

However, if he does not expect a significant decline in his tax bracket going forward, it will make sense to do the Roth conversion now.

I don’t know if any apply to the writer, but there are at least three other tax factors that need to be considered when doing a Roth conversion:

1) The 3.8% Medicare Surtax. Under the provisions of Obamacare, there is a 3.8% Medicare surtax on investment income earned by couples filing jointly with a modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) of more than $250,000 (or $200,000 for single filers). You’ll want to be careful that the amount of the Roth conversion won’t trigger that tax.

2) If You Have Company Stock in Your 401(k) Plan. The writer wants to convert his 401(k). That raises the possibility that the plan contains company stock. There are special rules that apply to net unrealized appreciation (NUA) of appreciated company stock in a company plan. Since the writer is over age 59 1/2, those rules would allow him to take a lump sum distribution from the 401(k) and pay the income tax only on the actual cost of the stock. He can sell the stock at a later date, paying only the long-term capital gains rate. This may cost him less in taxes than doing the Roth conversion.

3) Pay the Tax Liability Out of Non-tax Sheltered Savings. If the writer wants to be able to convert the entire $50,000 to a Roth IRA, he will need to pay the income tax liability out of taxable savings. For example, if he is in the 25% tax bracket, he will have to pay $12,500 in taxes. If he pays this out of the conversion amount, only $37,500 will make it to the Roth. By paying the tax bill out of taxable savings, he can convert the entire balance.

Final Thoughts – Addressing the Writer’s Specific Questions

Now that we’ve covered the basics of doing a Roth conversion after retirement, let’s get to addressing the writer’s specific questions.

The writer asks if he can do the following:

Move $50k from the 401K after the 4th Q distribution (so I get that income), but before year end? Assume distribution is 12/23, get distribution, then move 401K 12/28 for the tax hit this year.

Move $50k from 401K sometime next year for tax hit next year. I may move more depending on how the tax hit plays out, will analyze that.”

The answer to both questions is virtually the same. He can certainly do this, and it makes a lot of sense to spread the conversion out over several years. There’s $300,000 sitting in his 401(k), and the tax consequences of moving all at once can be overwhelming. It’s better to do the conversion on the installment plan when that kind of money is involved.

If he were to attempt to move the entire 401(k) balance of $300,000 in one year, it could push his combined federal and state income tax liability to somewhere between 40% and 50%. Paying upwards of $150,000 in taxes for the privilege of having tax-free income in the future is too steep a price to pay, even for that benefit.

By making annual conversions of $50,000, the transfer should be subject to much lower tax rates, enabling him to move more of money into the Roth.

This is what I meant when I said earlier that the tax implications of a Roth conversion aren’t always a pure play. Much depends on your income tax bracket and on the amount of funds that you are converting to a Roth.

In all likelihood, however, the writer will be able to set the conversion up in a way that keeps his tax liability to a minimum and accomplishes the goal that he hopes it will.